“Christ was subject to great humiliation in his private life at Nazareth,” writes Jonathan Edwards. While many of us can appreciate a great high priest who can “sympathize with our weaknesses,” the grittiness of this reality can escape us.

Edwards, the great theologian, writes of the daily toil of Christ’s vocation in Nazareth:

He there led a servile, obscure life, in a mean, laborious occupation; for he is called not only the carpenter’s son, but the carpenter. By hard labor he earned his bread before he ate it, and so suffered that curse which God pronounced on Adam; “By the sweat of your face you shall eat bread.”

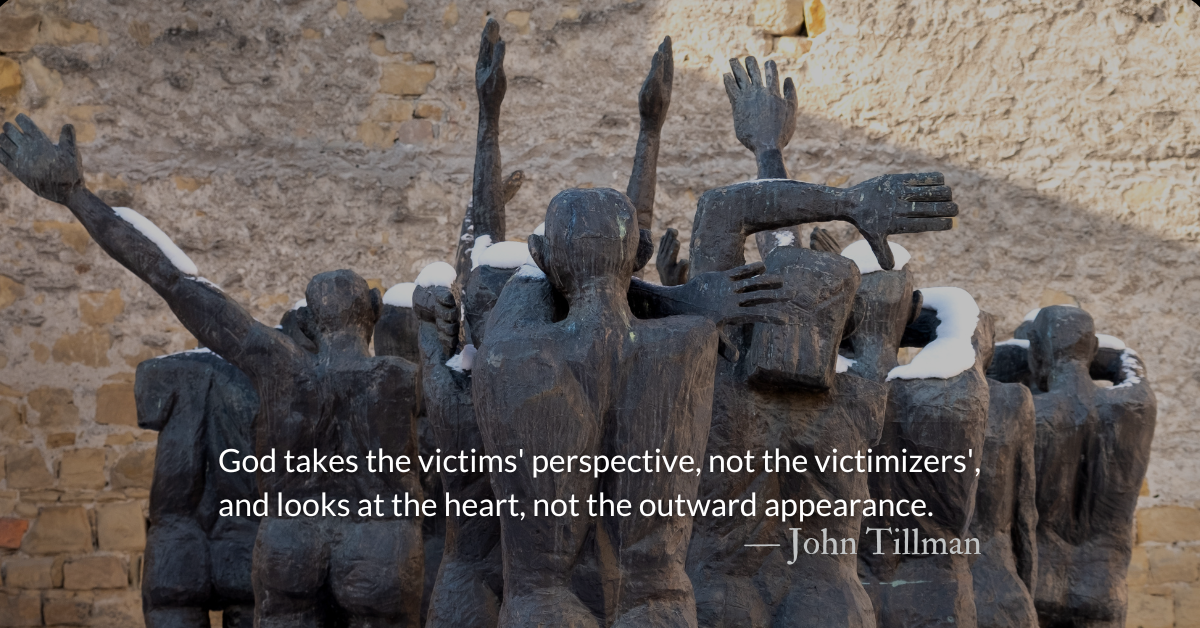

Let us consider how great a degree of humiliation the glorious Son of God, the Creator of heaven and earth, was subject to in this—that for about thirty years he should live a private obscure life among laboring men, and all this while be overlooked, not taken notice of in the world, more than other common laborers.

Christ’s humiliation in some respects was greater in private life than in the time of his public ministry. The first thirty years of his life he spent among ordinary men, as it were in silence. There was not any thing to make him to be taken notice of more than any ordinary mechanic.

In fasting we forego a luxury in order to better understand our desires and better experience the only one who can truly satisfy. The sacrifice of fasting is our way of entering into the footsteps of Christ who, “though he was rich, yet for your sake he became poor.” Edwards reflects on the fulfillment of Christ’s love, even as he was subjected to the pangs of earthly brokenness:

He suffered great poverty, so that he had no where to lay his head. So that what was spoken of Christ, “My head is filled with dew, and my locks with the drops of the night,” was literally fulfilled. And through his poverty he was doubtless when tried with hunger, thirst, and cold.

Christ had no land of his own, though he was possessor of heaven and earth; and therefore was buried by Joseph of Arimathea’s charity, and in his tomb, which Joseph had prepared for himself.

Christ being thus brought under the power of death, continued under it till the morning of next day but one. Then was finished that great work, the purchase of our redemption, for which such great preparation had been made from the beginning of the world.

Today's Reading

Job 32 (Listen – 2:12)

2 Corinthians 2 (Listen – 2:13)